Man Causes Lesbian Punch-Up

Fists and tomatoes fly at the 11th Women and the Law Conference

It was undoubtedly all a bit of a shock. What was meant to be a celebratory concert for the 11th Women and the Law Conference held in San Francisco, Feb. 28–Mar. 2, 1980, descended into a scene of chaos, confusion, and flying produce. The event, featuring renowned artists Sweet Honey in the Rock, Linda Tillery, and Mary Watkins, quickly became the epicentre of a heated controversy that left the local women's community reeling and questioning its core values.

Eyewitnesses reported a surreal scene at the Civic Auditorium, where approximately 4000 attendees gathered for what they thought would be an evening of empowering music. Instead, they found themselves in the middle of a small riot, with objects hurled at performers, heated verbal exchanges, and even physical altercations.

"I have never felt so physically intimidated by a crowd in my life," said producer Ellen LaCroix, who found herself surrounded by an angry mob of women in the foyer. The situation escalated to the point where Conference organiser Sally Kilberg was reportedly slapped in the face by a protester.

What could possibly have sparked such chaos at an event dealing with women and the law? The answer, it seems, lay in an unexpected addition to the evening’s lineup.

As Linda Tillery and her band took the stage, it became clear that something unexpected was afoot. A male musician had joined the ensemble. This seemingly innocuous personnel change sparked an immediate and visceral reaction from a vocal minority of the crowd.

Shouts of "Get the prick off the stage" and "Pricks shouldn't play lesbian music" echoed through the auditorium, accompanied by a small barrage of projectiles including tobacco butts, bottles, and yes, even tomatoes. The presence of the latter led some to question whether the disruption had been premeditated.

Notwithstanding its absurdity, the controversy did expose deep-seated tensions within the women's community, particularly around issues of lesbian separatism and racism. A number of separatist attendees felt betrayed, having expected an all-female lineup at what they (incorrectly) believed to be a women-only event. Others were appalled by what they saw as a racist and anti-feminist reaction to a primarily Black women's performance.

"It really grossed me out to be a Black performer and to be heckled by white women," Tillery stated, drawing a chilling comparison to historical accounts of violence against Black performers. "It reminded me of stories Bessie Smith told about the ropes of the tent she was performing in being cut by the Klan, who'd then lynch a few [redacted] for fun."

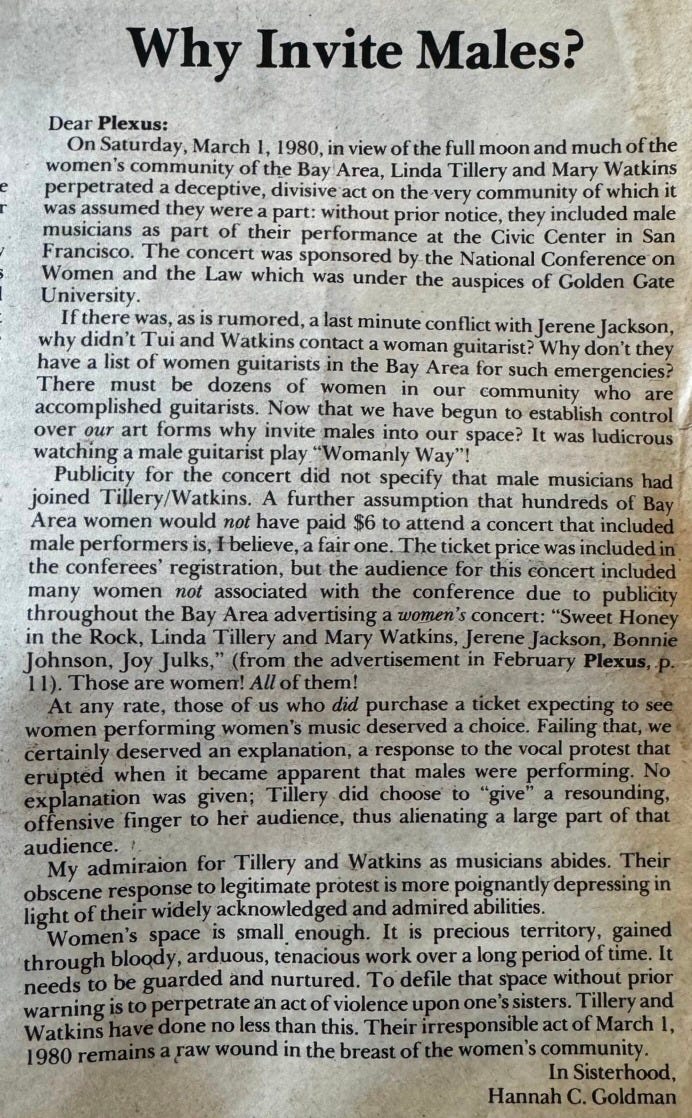

The incident sparked a flurry of impassioned letters to a local feminist publication, Plexus (April 1980), with opinions ranging from staunch defence of separatist ideals to vehement condemnation of the protestors' actions.

One letter writer, Hannah C. Goldman, argued that the inclusion of a male musician without prior notice was "a deceptive, divisive act" that defiled precious women's space, constituting “an act of violence” against the sisterhood. "Women's space is small enough. It is precious territory, gained through bloody, arduous, tenacious work over a long period of time," Goldman wrote.

Judy Freespirit and Andrea Land complained bitterly that women had been “assaulted by the presence of a man who was on the stage unannounced”. Even worse than that, Linda Tillery had condemned their protest from the stage, and then flipped them the finger. “Never in our memory has such disregard and downright hostility been shown to an audience by performers who are supposed to be part of our community,” they wrote. Freespirit and Land finished their letter by demanding a public apology “to all women who have been assaulted prior to this night, who have been abused, raped and impinged upon by men in the past.”

On the other side of the debate, artist Avotcia didn't mince words, describing the disruption as a "fascist tantrum" and questioning whether the protestors had "ever heard of a woman's right to work & freedom of creativity for the artist?"

The Women Writers Union also weighed in, condemning the "despicable attack" on the performers and suggesting that the separatist stance ignores other forms of oppression such as racism and class issues. "Are they so threatened by the presence of one man?" the union's letter asked.

The controversy did raise important questions about artistic freedom, and the intersection of various forms of oppression within the women's movement. Some argued that the reaction to the male musician's presence did reveal a troubling undercurrent of racism in the then predominantly white lesbian feminist community.

The group Zulema pointed out that the incident was part of a larger pattern of confrontation between, in their words, Third World women musicians and the women's community. They argued that the separatist stance was particularly problematic for Third World women, who could not afford to separate themselves from men in their communities while fighting against racism.

As the dust settled on the evening’s events, the women's movement was left grappling with difficult questions about its values, priorities, and the best way to move forward. Writing in Gay Community News, a couple of months later, Lee Swislow, who had been present at the event, offered these reflections on what had occurred:

[W]omen have repeatedly attacked other women in the movement. A small group of women have crossed the line from oppressed to oppressor. They have gained power at others’ expense.

We can look back in history… and see other examples of movements perverted by a leadership more into power than the principle of treating each other with decency and dignity. A movement will not lead to real change and a good society if it does not begin with basic kindness and humanity towards others. (GCN, 17 May 1980. p. 10-11)

Another concert-goer, Denise Wager, expressed the same basic point, but more succinctly, “I think we owe our women performers respect, and if these women said it was okay for a man to perform with them I think we should trust their choices."