Philosophers Scandalised by Tory MP

A philosophical pile-on in slow motion.

This is a curious story from the tail end of Margaret Thatcher’s tenure as prime minister of the United Kingdom. The context is the death of A. J. Ayer in June 1989, and the flurry of newspaper tributes that appeared in the immediate aftermath. Not the sort of thing likely to cause a kerfuffle, you might think, except an obituary written by Richard Wollheim for The Independent newspaper signed off with the following paragraph:

In the days when British life was still permeable to wide-ranging, free-floating argument, which endured until the late 1970s, Ayer made himself heard on a number of social issues. He was thought of, sometimes dismissively, as a voice of the liberal establishment. But on no issue was it a voice that could be disregarded. It based itself on fundamental principles and it exemplified an honesty of argument that is now in very short supply in the public domain. (The Independent, June 29, 1989, p. 1)

If you know anything about 1980s Britain, you’ll straightaway recognise this as a fairly typical dig at the politics of Thatcherism. If you’re a Tory MP, your best bet is just to ignore this sort of thing—after all, how many among the voting public actually care what a moral philosopher working in California thinks about—well, anything, really? But apparently Robert Jackson, Minister for Higher Education, just couldn’t quite help himself. He shot back as follows:

I guess it was only to be expected that one of Sir A J Ayer's academic obituarists should remark, as does Professor Richard Wollheim, upon the contrast between today's supposed intellectual ice-age and "the days when British life was still permeable to wide-ranging, free-floating argument, which endured until the late 1970s".

Equally, it is to be expected that those of this opinion will overlook the irony of such a contrast when it refers to a philosopher whose main work enormously narrowed the range of philosophical inquiry, and who taught, in Richard Wollheim's own words, that "all other thinking... religion, ethics, metaphysics... is literally meaningless... nonsense."

Wollheim's contrast between today's intellectual climate and that of Ayer's heyday is not, as he thinks, one between breadth, pluralism and openness on the one hand, and narrowness and dishonesty of argument on the other. His is the voice, rather, of a dethroned hegemony—dethroned largely because of the poverty and superficiality of its thinking.

This little missive did not go down well with the great and the good of British philosophy. Not in the least bit. Luckily for Jackson, it would be another 20 years before the invention of social media, so his savaging occurred in slow motion via the letters pages of The Independent.

G. R. Grice was the first in on the act, drawing a large lesson from the fact Jackson had used the word “taught” in his letter:

Of course, the other possibility here is that Jackson used the word “taught” because that's a perfectly normal shorthand to describe the act of arguing for a position. But that doesn’t seem to have occurred to Grice.

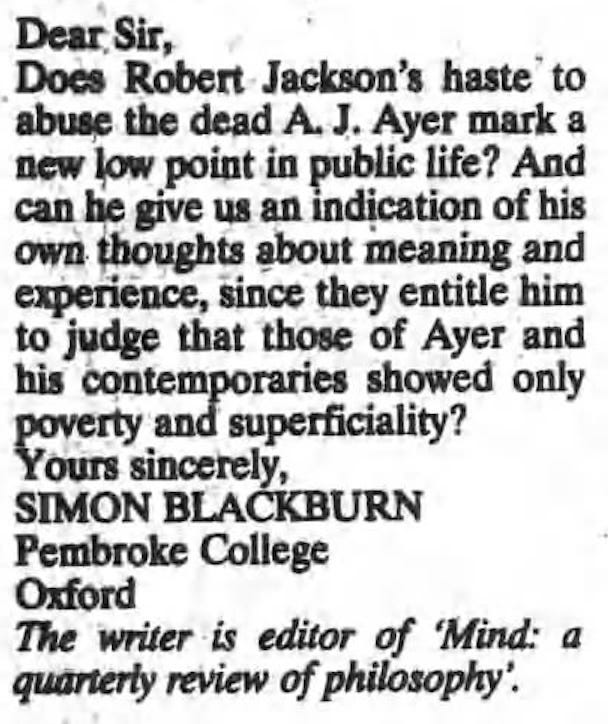

Simon Blackburn, for his part, upped the ante by asking whether Robert Jackson’s intervention marked a new low point in public life. (Probably a bit of a stretch, given Oswald Mosley, John Profumo, Jeremy Thorpe, the assassination of a prime minister, Richard III…).

Ronald Dworkin’s intervention was much more sober, and included an entirely proper analysis of the importance of being wrong in an interesting way.

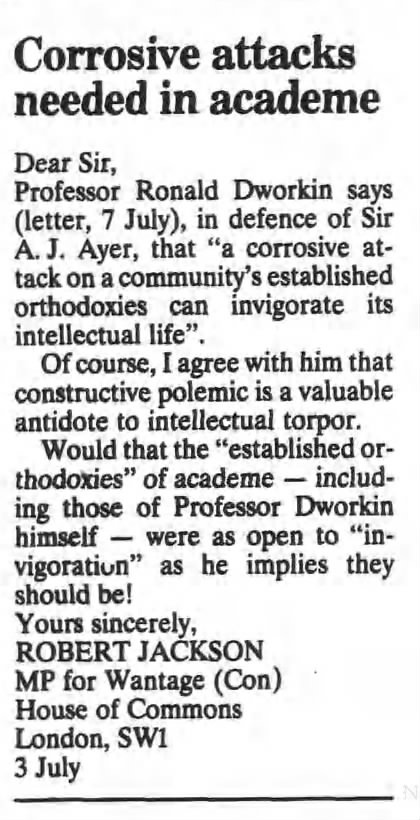

Obviously, Mr Jackson felt obliged to respond to the brickbats aimed in his direction, making the entirely correct point that the Academy isn’t quite so open to heterodox viewpoints as his critics seemed to think.

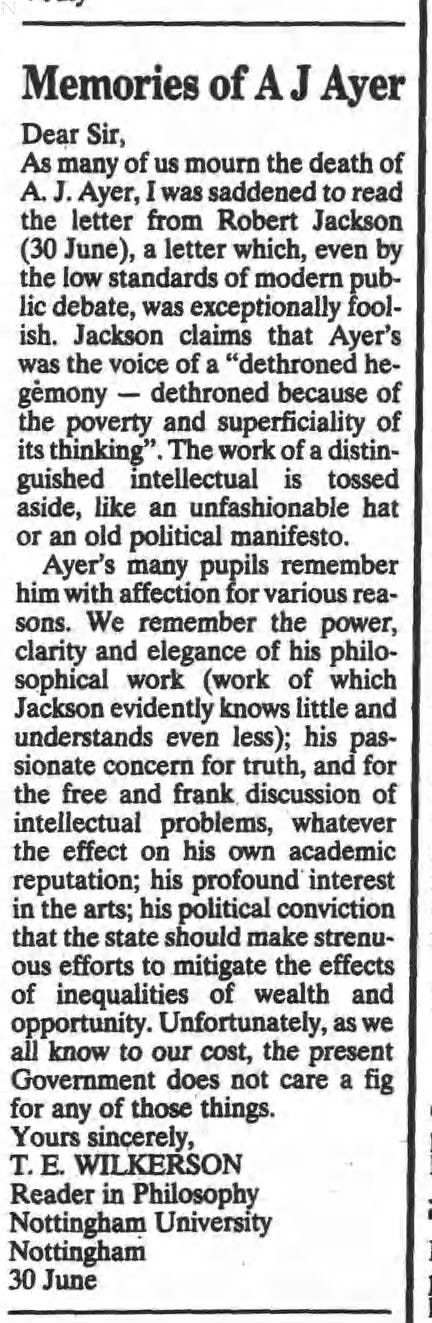

Next up was T. E. Wilkerson, complaining that Ayer’s ideas had been tossed away like an unfashionable hat, while at the same time rather confirming Jackson’s point about “established orthodoxies”, by making a sweeping claim about what everybody knew to their cost about the Conservative government.

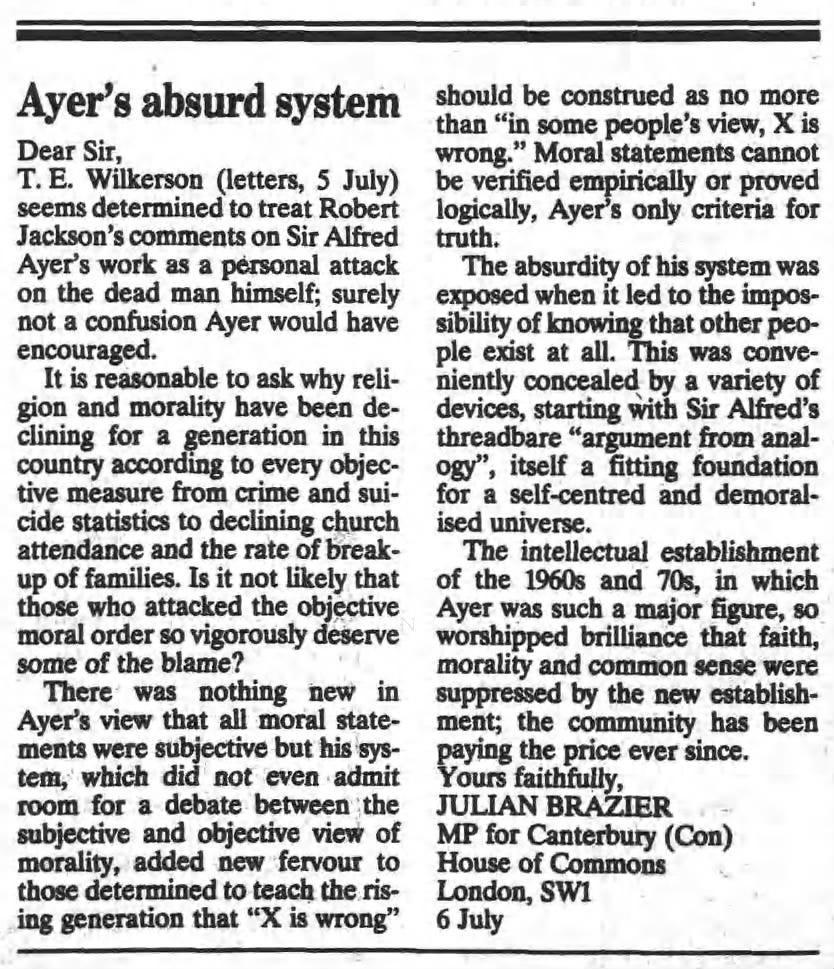

Team Jackson, however, was not for turning. Julian Brazier, MP, leapt onto the battlefield brandishing the traditional cudgels of Conservative thought: faith, morality and common sense.

The final substantive philosophical contribution was, surprisingly enough, measured in tone. Timothy Sprigge argued that it just isn’t true that Ayer considered moral philosophy and moral judgement to be meaningless:

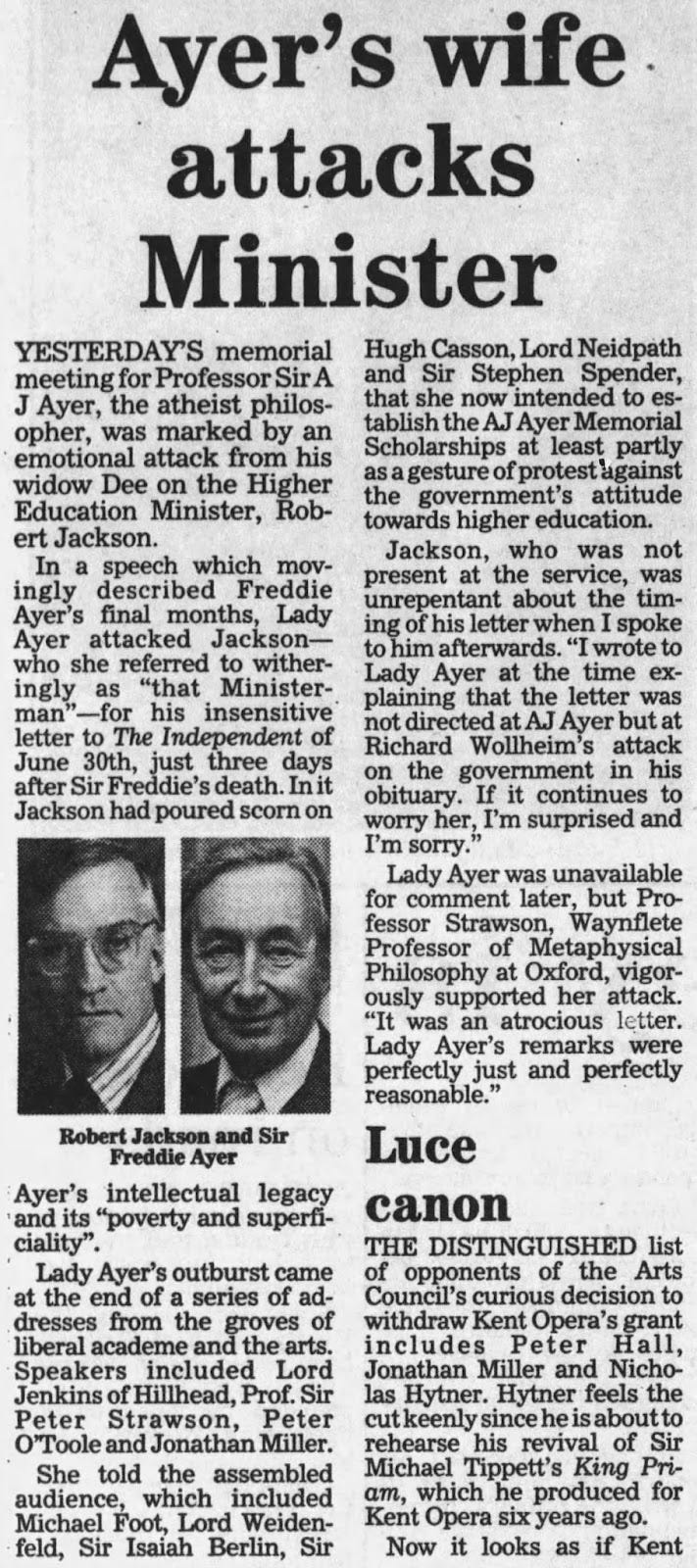

In terms of the letters pages of The Independent, that was it. But the whole affair rumbled on for a bit.

Notably, Peregrine Worsthorne, writing in the Spectator, castigated Jackson’s critics for their “woefully misplaced” outrage. He insisted that the Ayer he knew would have had no time for such sentimentality. Moreover, he claimed that Ayer himself was insensitive in precisely the same way critics alleged of Jackson.

Shortly after learning that his beloved wife Vanessa was dying of cancer he wrote asking me—a friend of Vanessa’s—to put him up again for the Garrick Club…on the grounds that he would soon be in need again of somewhere to dine in convivial company. I can think of quite a few people unselfless enough to be thinking of themselves in this way at such a time; but absolutely nobody other than Freddie would have been so insensitive as to try to translate such private thoughts into action. (Spectator, 15 July, 1989)

A week later, a letter from Jackson appeared in the Spectator, offering an important—and, I think, plausible (the subtext running through this entire brouhaha is outrage at the cuts to university funding for the humanities enacted by the Tories through the 1980s)—corrective:

…Perhaps I could correct Perry–and others–on a point of fact. My letter to the Independent was not, as he seems to think, an early shot in the debate about the value of Ayer’s work. It was, in fact, a criticism of a quite gratuitous piece of political banner-waving in the final paragraph of Professor Wollheim’s front page obituary of Ayer in that newspaper. (Spectator, 22 July, 1989)

That should have been the end of the matter, but actually our tale has a postscript. In December 1989, the London Evening Standard ran the following story.

Peter Strawson’s claim that Jackson’s letter was “atrocious” and that Lady Ayer’s remarks were “perfectly just and perfectly reasonable” does rather lead one to wonder what he must have made of Roger Scruton’s article about Freddie Ayer, published in the Sunday Telegraph on July 2nd, less than a week after Ayer’s death, in which Scruton had this to say about Ayer:

…Ayer was the very opposite of a philosopher. He was a hater of wisdom, a man devoted to destroying the conceptions in which the wisdom of humanity reposes, and replacing them with a disenchanted language of fact. And his morality, which he presented as a shocking defiance of established views, was a mere hotch-potch of unsupported platitudes.

Probably he didn’t like it.

Can we please return to a time when Conservative Party MPs were capable of this level of intellectual discourse

Here you go.

https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v11/n14/richard-wollheim/diary