What A. J. Ayer Saw When He Died

Logical-positivism vs. a near-death experience

In the summer of 1988, one of Britain’s most vocal atheists had an unexpected brush with mortality—or perhaps, immortality.

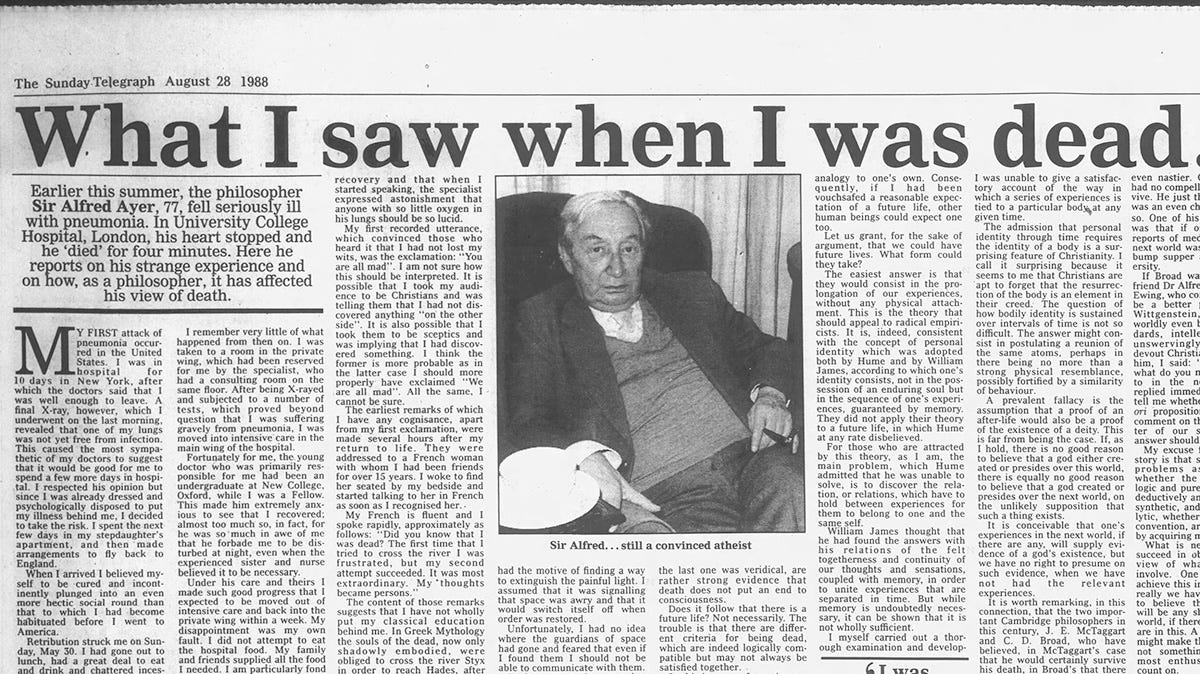

While recovering in University College Hospital following a bout of pneumonia, Sir Alfred J. Ayer, the philosopher whose logical positivism had helped to shape twentieth century philosophical thought, managed to choke on some smoked salmon that his friends had kindly delivered to him, and promptly “died” for four minutes.

An unfortunate occurrence, to be sure, made more troubling by the fact that it did not result in the immediate cessation of consciousness. The philosopher, who had once suggested that religious language is meaningless, underwent a quasi-mystical near-death experience. Here’s how he recounted it in the Daily Telegraph (August 28, 1988).

I was confronted by a red light, exceedingly bright, and also very painful even when I turned away from it. I was aware that this light was responsible for the government of the universe. Among its ministers were two creatures who had been put in charge of space. These ministers periodically inspected space and had recently carried out such an inspection. They had, however, failed to do their work properly, with the result that space, like a badly fitting jigsaw puzzle, was slightly out of joint.

A further consequence was that the laws of nature had ceased to function as they should. I felt that it was up to me to put things right. I also had the motive of finding a way to extinguish the painful light. I assumed that it was signaling that space was awry and that it would switch itself off when order was restored.

Unfortunately, I had no idea where the guardians of space had gone and feared that even if I found them I should not be able to communicate with them. It then occurred to me that whereas, until the present century, physicists accepted the Newtonian severance of space and time, it had become customary, since the vindication of Einstein's general theory of relativity, to treat space-time as a single whole. Accordingly, I thought that I could cure space by operating upon time.

I was vaguely aware that the ministers who had been given charge of time were in my neighborhood and I proceeded to hail them. I was again frustrated. Either they did not hear me, or they chose to ignore me, or they did not understand me. I then hit upon the expedient of walking up and down, waving my watch, in the hope of drawing their attention not to my watch itself but to the time which it measured. This elicited no response. I became more and more desperate, until the experience suddenly came to an end.

Ayer was sufficiently discombobulated by his unexpected visit to the twilight zone that he devoted a large part of his Telegraph article to analysing what it would mean for a mind to survive the death of the body. He admitted that while the experience hadn’t converted him to a religious viewpoint, it had “slightly weakened” his conviction that his genuine death would be the end of him.

A couple of months later, presumably as the philosophical equivalent of buyer’s remorse began to kick in, Ayer retreated a little from this new unwelcome woolly-mindedness. In a postscript published in The Spectator, he clarified that what had weakened was "not my belief that there is no life after death, but my inflexible attitude towards that belief."

It was a distinction that only a philosopher could make—and, thankfully, perhaps only a philosopher would feel compelled to make. But are we buying it? Sorry, Professor Ayer, but not really.

If a prison guard claimed they were just as certain as before that a cell door was locked, but were now more open to checking it, we'd suspect their certainty had taken a knock. It is surely the same story here. If a person is genuinely open to testing a belief—not just going through the motions, but really allowing for the possibility they might be wrong—then they've already moved from certainty to probability, however high that probability might be.